Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs) have skyrocketed in popularity over the past 18 months. This post explores what SPACs are, the history of SPACs, and some of their positive and negative attributes.

A SPAC, sometimes referred to colloquially as a “blank check company,” is a shell company set up by investors with the intent of raising money through an initial public offering (IPO) for the sole purpose of acquiring a private company.

At the time of creation, the initial company has no operations, with the only asset being balance sheet capital raised through the IPO. In most cases, SPACs are managed by institutional investors such as hedge funds, investment banks, private capital funds, or dedicated SPAC vehicles. Underlying acquisition targets are not formally pursued until after the formation of a SPAC is completed.

Once a SPAC goes public, the capital raised is placed in a trust and the SPAC has a defined period of time, most commonly two years, to acquire and merge with a company. If a company is not acquired within this time frame, the original capital , plus any interest accumulated through the trust, is then returned to investors. After a target company is identified, shareholders of the SPAC have the opportunity to either remain a shareholder of the post-merger company, or receive their pro-rata share of the funds held in the trust account. After the approval and completion of the acquisition, the SPAC evolves into an actual operating company.

A prominent example of a successful SPAC was Flying Eagle Acquisition Corp., which completed a $600 million initial public offering in March 2020. In April 2020, the SPAC announced it would be acquiring and merging DraftKings, a U.S. sports betting company, and SBTech, an online gaming platform that provides technology to sports books. The company, which kept the name DraftKings (NASDAQ:DKNG), has experienced a share price increase of more than 600% since the merger.

The SPAC was initially used by GKN Securities in 1993 and David Nussbaum, the firm’s chairman and CEO at the time, is frequently attributed as the creator of the vehicle. GKN launched 13 SPACs, 12 of which successfully acquired a company, between 1993 and 1994. Subsequent legal troubles faced by the firm delayed the adoption of SPACs by other market participants.

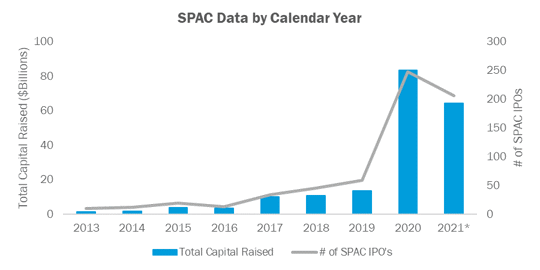

SPACs were utilized infrequently until 2005, when total capital raised by SPAC IPOs first surpassed $1 billion. This number increased to $12.1 billion in 2007 before decreasing substantially after the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. A resurgence began in 2013 with 10 SPAC IPOs representing $1.4 billion of proceeds, followed by relatively slow, consistent growth until an explosion in 2020 as depicted by the graph below.

Exhibit A. Source: SPAC Analytics as of March 3, 2021.

Last year was a record year for SPACs, with the number of SPAC IPOs and total capital raised increasing by 420% and 513%, respectively, compared to 2019. In fact, there were more SPAC IPOs in 2020 than in the previous 12 years combined. These numbers are on pace to be decimated in 2021, however, as there have already been 207 SPAC IPOs representing $66.4B of total capital raised in just over two months.

As with direct listings, which have also grown in popularity in recent years, SPACs are an alternative way for a company to go public. There are advantages of SPACs from the perspective of shareholders of the acquired company, as well as investors in the SPAC.

For the company being acquired, exiting to a SPAC as opposed to traditional IPOs is attractive for a variety of reasons. For one, the selling process is faster and easier due to negotiating with a single buyer rather than a broad process run by an investment bank. The company can also avoid underwriting fees, legal and tax expenses, and strict disclosure guidelines and timing windows required for a traditional IPO. Additionally, while company shareholders are not able to cash out 100% of their equity stake in a sale to a SPAC, they can frequently share in favorable economics with the deal sponsor, often through the transfer of a portion of founder shares in connection with the sale. On the private capital side, Canterbury has predominately observed venture capital managers utilizing SPACs for exit purposes.

Investors in a SPAC are able to gain exposure to in-demand, mature private companies with a defined net asset value, unlike the challenge of investing in a company immediately post-IPO, where there are often dramatic price swings in the first hours or days. Investors also possess optionality through redemption rights: If the deal presented by the sponsor is deemed unattractive, then the option exists to redeem at cost. There have been some significant winners in the SPAC space, according to performance data from SPAC Analytics as of March 3, 2021, such as DraftKings (687% return), Betterware (585%), Iridium (570%), QuantumScape (501%), and MP Materials (408%).

While the headlines highlight SPACs that have generated massive returns for investors such as those listed in the previous paragraph, SPACs have not always outperformed. Johannes Kolb and Tereza Tykvova from the University of Hohenheim completed an analysis of SPAC IPOs between 2013 and 2015 in a 2017 paper titled “Going Public via Special Purpose Acquisition Companies: Frogs Do Not Turn into Princes.” In the analysis, Kolb and Tykvova asserted that SPACs lagged both the overall stock market and traditional IPOs from a performance standpoint. Furthermore, Michael Klausner, Michael Ohlrogge, and Emily Ruan’s 2020 paper titled “A Sober Look at SPACs” states: “first, for a large majority of SPACs, post-merger share prices fall, and second, that these price drops are highly correlated with the extent of dilution, or cash shortfall, in a SPAC.” The paper goes on to propose regulatory measures to eliminate current preferences that SPACs receive and increase SPAC transparency.

The fee structure of SPACs is also lofty. There is generally a flat fee of 5% to 6% comprising underwriting fees at the time of the SPAC IPO and at the completion of the merger, which in itself compares favorably to IPO processes (typically 7% of proceeds raised). The most impactful, however, is the promote, in which the sponsor receives shares, commonly 20% of what the SPAC bought, as an incentive fee. For example, if a SPAC raises $100 million and spends the full $100 million acquiring a company, the company provides an additional $20 million worth of shares to the sponsor and company executives, diluting other investors in the transaction as referenced in the prior paragraph.

The prevalence of SPACs has increased dramatically over the past two years, and only time will tell how performance of these vehicles will compare to other investment opportunities over the long term. SPACs can be a useful tool for private capital managers, particularly venture capital managers, to exit portfolio companies through the public markets while avoiding the complexities of a traditional IPO, and certain SPACs have generated meaningful outperformance. At the same time, investors contemplating exposure to SPACs should make sure to consider the risks, as well as the high fees and promote, prior to making an investment, with manager selection being the most important criteria.